© Royal College of Physicians

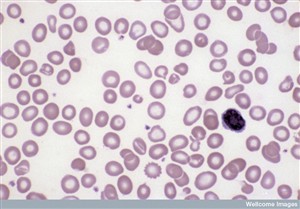

Blood cells showing iron deficiency anaemia

Photograph courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London

Honorary Physician

By Claudia Jessop

During the first half of the 20th century, paediatrics was something of a ‘Cinderella’ discipline owing to its relative newness – the field of neo-natology, in particular, was in its infancy. This meant that it was not an established part of the (male-dominated) medical landscape of venerable institutions, time-honoured career trajectories and permanent positions. It therefore attracted a high proportion of women doctors – their male colleagues were more likely to want to benefit from the status and earning opportunities of more well-established branches of medicine. It was impossible for women to train in any major hospitals (with the sole exception of the Royal Free which had established its School of Medicine for Women in 1874), or to be admitted as trainee paediatricians to the centre of the paediatric discipline, Great Ormond Street Hospital. Despite this, several women managed to benefit from the discipline’s marginal status within medicine, which made its boundaries more permeable to them than was the case with some other disciplines, and from the fact that for many of them, the shortage of men during the First World War around the time that they qualified provided a timely career-boost, allowing them access to institutions that were forced in desperation to admit them, their doors being firmly closed in peacetime. Several of these women went on to forge distinguished careers and to conduct research that would change the way child health was viewed forever; the discipline was dominated by women in the pre-NHS era. One of the earliest and undoubtedly one of the most eminent and influential of all these women paediatricians was Dr Helen Mackay, whose clinical practice was one of the pivots of the Mothers’ Hospital for 40 years, and whose research work is still referred to today. She was one of the team of women around which the Mothers’ Hospital revolved during the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s, and appears to have been, both professionally and personally, a woman of complete dedication and dependability.

Early life and career

Born in Inverness on 23 May 1891, Helen Marion Macpherson Mackay was the second of three children and the only daughter of Duncan Lachlan Mackay of the Indian Civil Service and Marion Gordon Campbell Mackay (née Wimberley). Her childhood was spent in Burma, where she was educated at home, and at the age of 15 she went to Cheltenham Ladies’ College. She trained at the London School of Medicine for Women at the Royal Free, qualifying MRCS, LRCP, MB BS in 1914. She became MRCP and MD in 1917. In1919 she became the first female house physician and surgeon at Queen’s Hospital for Children in Hackney Road. She was to continue to work there, as well as at the Mothers’, for 40 years, becoming one of the first female consultants in any speciality, and the very first in London outside the Royal Free. In 1920, Mackay became the first Honorary paediatrician to the Mothers’ Hospital. Between 1926 and 1959 she was the Hospital’s Physician-in-Charge of Neo-Nates. In addition to these posts, she was also consultant paediatrician at Hackney Hospital (the first to hold this post) and at the General Lying-in Hospital in York Road, Lambeth. She also did consultancy work at Thorpe Coombe Maternity Hospital in Forest Road, Walthamstow between its opening in 1934 and 1948, and was editor of the magazine of the London School of Medicine for Women.

One of the most important moments of her career came in 1934, when she became the first woman to be elected as a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. From 1933-5 she was also secretary of the Diseases of Childhood section of the Royal College of Medicine, and from 1944-5 its president. She was on the staff of the Medical Research Council between 1928 and 1951.

Her long career was stellar to its end. She became a consultant paediatrician to the London County Council, and in 1944 was elected president of the paediatric section of the Royal Society of Medicine. Following the establishment of the NHS, she was one of the founder members of the North-Eastern Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board. In 1945, she was one of five female paediatricians permitted to join the British Paediatric Association. They were the first women to be allowed to join.

She is considered to have provided inspiration to a generation of important women paediatricians (including Cicely Williams with whom she worked at the Queen’s Hospital).

Mackay was evidently viewed with real affection and with the highest respect in the community of Hackney which she served for so long. Her calm manner and her way of soothing distressed babies and their mothers became legendary amongst patients, as did her beautiful handwriting and meticulous record-keeping amongst staff. She was a distinctive figure, dressed every day in the identical, austere brown suit, tie and trilby hat, which became her trademarks. The laboratory scientist Laurel Goodfellow, with whom she collaborated on one of her first papers on anaemia, became her companion and life-long partner. Her passions outside medicine were ornithology, gardening and the Scottish Highlands, where she spent regular holidays. She died of a stroke in the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital on 17 July 1965, and was buried at Golders Green Crematorium.

She seems to have impressed her peers with her compassion, and with her interests in the idea of community care and social service. Her obituary in the British Medical Journal in 1965 stated that “she was never dispassionate, and the pattern of her mind was womanly.”

Dietary deficiency, rickets and the children of Vienna

Mackay’s study of infantile anaemia, which was to become the focus of her seminal research work and the area in which she was to leave her most important and enduring mark, grew out of her earlier work on another disease of dietary deficiency – rickets. Both diseases were strongly associated with poverty of the kind that Mackay encountered in her work at the Mothers’. We now know that rickets is caused by a deficiency of calcium in the bone; this in turn is caused by inadequate levels of calcium and/or Vitamin D in the diet, and/or by inadequate exposure to sunlight, which the body needs in order to absorb Vitamin D. (The condition, and specifically the link with Vitamin D, was not fully understood until the 1930s.) The deficiency in this case is of calcium: the disease causes children’s bones – which require high levels of calcium relative to adults’, because of growth – to soften, causing bending of the spine, bowing of the legs, and malformations of the jaw, which become permanent once the child has finished growing. It was still a very common condition in the early 20th century, especially amongst poor urban children who, as well as having inadequate diets, were often deprived of sunlight while they worked long shifts in enclosed factories, returning home to overcrowded and polluted streets. Once the link with sunlight deprivation had been discovered, charitable organisations began to organise trips for such urban children to the countryside in the summer. (The famous "Daddy Burtt's" of Shoreditch - officially known as the Hoxton Market Christian Mission - funded seaside and countryside trips for 662 children and other days out - mainly to Epping forest - for almost 10,000, in just one year in the 1920s, which gives a sense of the enormous need for such healthy outdoor activities for the many poor urban children who would have had no other opportunity to enjoy them. Many children's nurseries and facilities in the inter-war years celebrated the healthy properties of sunshine with names like "Sunshine Babies", and architects explored designs for sun-balconies in homes and hospitals - like those in the German Hospital's modern wing.) It is an indication of dietary improvement over the last generation or two that the deformities of rickets, still common well within living memory, are no longer seen in communities like Hackney.

In 1920, Mackay was awarded a Beit Memorial Fellowship by the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine. As a result of this, she went to Vienna as part of a team from the Institute, under the auspices of the Medical Research Council, led by Harriette Chick. The team’s three-year mission was to “study the aetiology of the deficiency diseases”. It is easy to underestimate the severity of the dietary deficiencies being suffered in the Austrian capital when Mackay was working there in the aftermath of the First World War, and the prevalence of the diseases we now understand to be associated with these deficiencies. Young children like those Mackay’s team studied were particularly affected although not exclusively – many adults had also developed the painful and crippling disease osteomalacia, a hitherto unknown condition which seemed to be the adult equivalent of rickets. In 1919, studies had established that 96% of Viennese children were undernourished – food shortages were dire, and had prompted relief missions by the US government, and the Society of Friends of both Britain and America. The undernourishment of both adults and children affected all classes of society, including the professional and previously well-to-do (the American Relief Administration provided free meals to undernourished professors at several Austrian universities). The dire food shortages and consequent dietary crisis affecting Vienna in 1919 afforded an important opportunity for those, like Mackay, who were committed to the study of infant health, to study malnourished children in large numbers and across all age ranges and backgrounds. Rickets was almost universal among the children of Vienna, a large percentage of whom also suffered from scurvy, and whose mental and physical development was often found to be severely delayed. It was an interesting time for such work as Mackay and her colleagues were undertaking – the conflict between different schools of medical thought on the causes of rickets was at its height, with those who believed in dietary and those who favoured environmental causes engaged in a vigorous debate (the cause was subsequently discovered to be a combination of the two). The research was conducted at the Kinderklinik at the University of Vienna, under Professor Clemens von Pirquet, who had been put in charge of administering the American relief effort. Though sceptical about the new theories of nutrition, Professor von Pirquet allowed the British researchers a free reign to study his young patients. Fifty infants were observed for periods ranging from five to 15 months – half received the clinic’s standard diet and half a diet devised by the British researchers which included more milk, less sugar, and cod liver oil.

The research established the link between diet and rickets, and led to new understanding of its prevention and cure, showing that cod liver oil was effective, and also demonstrating the importance of sunlight. Its findings were published in 1922 as Studies of Rickets in Vienna 1919-22, a report for the Medical Research Council. A quarter of a century later, the research Mackay and her colleagues Chick, Dalyell, Hume, Smith and Wimberger undertook was referred to by agencies seeking to alleviate the malnutrition being suffered in formerly occupied Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War.

It was while conducting this study in Vienna that Mackay first became aware of the prevalence of infantile anaemia, and interested in understanding its aetiology and epidemiology more deeply. This interest was to lead to her groundbreaking work on the subject, conducted with infants at the Mothers’ Hospital, whose influence continues to be felt today.

Anaemia and iron deficiency

Mackay’s work on infantile anaemia did three unprecedented and extremely important things: it showed conclusively that dietary iron deficiency was its commonest cause, it illuminated its epidemiology, and it led to a new awareness of how it could be prevented, and of the importance of this. The fact that more than 70 years after her studies were conducted, EU legislation dictates that all manufacturers of infant formula milk must add supplementary iron to their products is a direct result of Mackay’s findings – her legacy has affected the diets of two generations of children all over the world.

Anaemia is a potentially very serious health problem in children – although it usually responds well to treatment with iron supplementation after a couple of months, with numbers of red blood cells returning to normal (a treatment we owe to Mackay). We now know that chronic anaemia in children can have serious neuro-developmental effects, as well as debilitating symptoms like fatigue. It has been shown to cause deficiencies in motor and cognitive skills, poor concentration and behavioural problems, and sometimes these problems are not solved by treatment even when the red blood cell count is returned to a healthy level.

Mackay was concerned to discover that almost all of the children with whom she worked in Vienna were anaemic. After returning to Britain, she set about investigating the condition in the very young, studying her child patients at the Mothers’ and Queen’s Hospitals between 1925-7, having been awarded the Ernest Hart research scholarship. She found the condition to be endemic, and investigated the role of iron deficiency – during the 1920s the vast majority of East London children was deficient in iron. She established normal haemoglobin levels for different stages of infant development, which had not been done before; she was the first person ever to understand how haemoglobin developed in early infancy. After studying the haemoglobin levels of breastfed babies and those fed with both cow and formula milk, she concluded that breast milk lessened haemoglobin deficiency – she found that while 50% of the iron in human breast milk was absorbed by the infant, only 10% of the iron in cow’s milk was. She experimented with various therapeutic and preventative approaches including light- or helio-therapy (then beginning to be very fashionable) and iron supplementation. She concluded that babies who were not being breastfed should be given supplementary iron, and this is still received wisdom today (see formula milk fortification, above). At the Mothers’ she prepared an iron sulphate preparation which the staff dubbed “Mist Helen Mackay”, and she urged that it should be given to all children suspected of iron deficiency anaemia.

The results of her studies were published in two groundbreaking reports: Anaemia in Infancy: Its Prevalence and Prevention (Ministry of Health, 1928), and Nutritional Anaemia in Infancy with Specific Reference to Iron Deficiency (Ministry of Health, 1931). Her final study was published just after her retirement: Weight Gains, Serum Protein Levels and Health of Breastfed and Artificially Fed Infants (1959). Her definition of what constituted infantile anaemia was used by the World Health Organisation in its work on the subject in the 1960s.

In 1933, Mackay undertook another important study at the Mothers’ Hospital, to investigate haemoglobin function in the first months of life. She measured the haemoglobin levels of 150 babies born there, and looked at the effects of low birth weight on the findings. Her first attempt at preventing the anaemia involved taking blood from one of the child’s parents, and injecting it into the baby. This was unsuccessful, so she went on to try giving the affected babies orally, a preparation of iron and ammonium citrate. Unfortunately, this proved unsuccessful too, but in the course of her experiments, Mackay was able to establish for the first time what “anaemia of prematurity” consisted of, and to rule out iron administration as a possible prevention.

During the Second World War, when food shortages exacerbated iron deficiency, Mackay continued to study anaemia in mothers and children. In 1941, she published Calorie Requirements of Full-Term and Premature Infants: A Formula.

In understanding how radically Mackay transformed the landscape of understanding of infantile anaemia, it is important to note that when she began her work on it, there was still no accepted definition of the condition. There had been no successful studies carried out to establish how and why it affected infants, or how often. No one prior to Mackay had managed to establish reliable figures for haemoglobin concentrations in babies.

Throughout her career, working mainly with the poor, Mackay was very concerned with the way in which social conditions affected child health, with poverty giving rise to environmental and deficiency-related causes of disease. With this in mind, she helped set up mother and baby clinics in the local community. Her work on dietary deficiency was made possible, and rendered more urgent, by the fact that amongst her patients in Hackney were some of the poorest and most disadvantaged children in the country, with the least adequate diets – during this period iron deficiency was as prevalent and as severe in Hackney as it now is in some of the poorest areas of the developing world (where it remains the most common micronutrient deficiency).

Overall, the problem has dwindled significantly over the intervening decades. In fact, as long ago as 1971 David Burman did a study on babies in Bristol, whose haemoglobin concentrations without being given supplementary iron turned out to be similar to those of the Hackney babies tested after Mackay had given them additional iron in the early 1930s. But while this improvement may apply to the population as a whole, iron deficiency still affects some of the poorest communities quite significantly – as late as the 1980s it was seen to be a problem for up to a quarter of children in some deprived inner city areas, and recent US figures show 9% of children aged 12-24 months to be deficient in iron. In many parts of the world, prevalence of iron deficiency amongst children has actually been increasing since the 1970s; it now stands at 43% worldwide.

An illustration of how Mackay was able to translate her dietary research findings into straightforward, accessible advice, and of how passionately she believed in the importance and therapeutic potential of the contemporary study of dietetics, was given in January 1932, when she addressed the winter school for health visitors and school nurses, arranged by the Women’s Public Health Officers’ Association, at Bedford College for Women, Regent’s Park. She explained how a deficiency of almost any constituent of a healthy diet could result in lowered resistance to disease, and went on to tell her audience how understanding of dietetics was developing at a pace, expressing the belief that many diseases would eventually be revealed to have dietary deficiencies as their cause, or one of their causes, opening up new and exciting possibilities for prevention and treatment. She expressed the particular conviction that diet was a factor in rheumatism and diseases of the middle ear (though she acknowledged that many differed from her in that belief). She emphasised the importance of good nutrition in childhood, and stated that “even the poorest mothers, if they realized what sort of diet they should aim at, could achieve wonders”. She set out her dietary formula for a healthy child between the ages of one and four or five: every day, the child should have a pint of milk, some meat, fish or eggs (at least two but not more than four eggs per week), and some fresh fruit, and should be exposed to as much sunlight and air as possible. It was a fashionable childcare practice at the time for babies and toddlers to be left outside in the open air in their prams, and Mackay encouraged this – but she warned against leaving the hoods of the prams up – this would prevent the sunlight getting to the child’s face.

Bibliography

Dr David Stevens, 'Pride, Prejudice and Paediatrics', Women Paediatricians in England before 1950, Archives of Diseases in Childhood, 2006

Dr David Stevens, 'Helen Mackay and Anaemia in Infancy – Then and Now', Historical Review, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1991

Dr David Stevens, Mackay, 'Helen Marion McPherson', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP 2009

Robert D. Christensen, 'The Anaemia of Prematurity', Origins of the Discipline “Neonatal Haematology, British Journal of Haematology, 2001

Elizabeth M. E. Poskitt, 'Helen Mackay and the Children of East London', Defining the Role of Iron Deficiency, Historical Review, British Journal of Haematology, 2003

Jennifer Worth, 'Rickets', Call the Midwife, Phoenix 2002

Andrea Bersamin, Karrie Heneman, Cristy Hathaway, Sheri Zidenberg-Cherre, 'Iron and Iron Deficiency Anaemia', University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources (www.%20Anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu, accessed November 2009)

Dr H Chick, 'Nutritional Researches in Vienna after the First World War', address to the Joint Meeting of the Association of Scientific Workers and The Workers’ Educational Association on Science and Post-War Relief, 11 March 1944 (www.journals.cambridge.org, accessed November 2009)

Mauro Batista de Morais and Dirce Maria Sigulem, 'Cow’s Milk, Infant Formula and Iron-Deficiency Anaemia', Jornal de Pediatria (www.scielo.br, accessed November 2009)

Richard R. Trail, 'Mackay, Helen Marion Macpherson' (www.rcplondon.ac.uk/heritage/munksroll, accessed November 2009)

Unknown Author, 'Dietetics and Disease: Dr Helen Mackay’s Advice to Mothers', The Times, 2 Jan 1932

Unknown Author, 'Dr Helen Mackay' (Obituary), The Times, 17 July 1965

Carolyn Clark and Linda Wilkinson, "The Shoreditch Tales", Shoreditch Trust 2009

This page was added by

Lisa Rigg on 09/02/2010.